Lessons from high-stakes environments for public service

By Si Ying Thian

Hong Kong Police veteran Peter Morgan says that public agencies must swap a reactive approach for a strategic one by scanning the horizons and being open-minded to borrow the best ideas from outside.

-1759378061977.jpg)

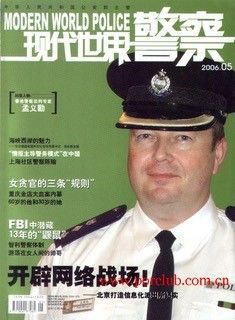

Peter Morgan is the Hong Kong Police Force’s Special Advisor of the Police Hostage Negotiation Unit, and has more than 27 years of experience in frontline crisis management, strategic leadership and organisational change in the police force. Image: Peter Morgan

For any large organisation, including public agencies, civil servants tend to focus on solving immediate problems as they operate under the reality of daily operational demands.

But according to the Hong Kong Police veteran Peter Morgan, this focus on daily tasks, while necessary, must not crowd out strategic thinking to tackle emerging challenges.

Morgan is the HK Police Force’s Special Advisor of the Police Hostage Negotiation Unit, and has more than 27 years of experience in frontline crisis management, strategic leadership and organisational change in the police force.

Drawing on his background studying history, he asserts a timeless truth that "there's nothing new under the sun": Almost every problem has already been addressed or contemplated by someone else, somewhere.

To effectively govern at highly uncertain times like these, public agencies must “borrow ideas with pride”, by being open-minded and willing to apply ideas already working elsewhere to their own jurisdictions, he says to GovInsider.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

Promote wartime leaders, not peacetime managers

Having spent 24 years as a hostage negotiator, he highlights that true leadership in a crisis is less about following a manual, but possessing the competence and conviction to risk being wrong to pursue the best outcome.

As civil servants go up the ladder, they tend to become quite risk-adverse to avoid jeopardising their careers, he notes, further highlighting the need for organisations to be more supportive of experimental leaders.

These are leaders who excel under pressure, and not just manage paperwork well.

In high-stakes situations, peacetime managers may be ill-equipped to take charge, remain in control, and make decisions based on complex, rapidly incoming information, he adds.

At highly uncertain times like these, it becomes ever more important for civil servants to build operational confidence and adaptability, instead of simply adhering to protocols.

Underlining the need for these next-generation skillsets among civil servants, Morgan illustrates this with an incident he had successfully intercepted as a hostage negotiator previously by going against the conventions.

Despite professional advice to end negotiations with the subject by implementing a high-risk tactical option, he used the subject’s uncle and his love for mahjong to prompt the subject’s peaceful surrender.

Cowardice as a disciplinary offense

Speaking up is especially challenging in rank-based environments like defence and home affairs.

Morgan, however, highlights the value of proactive communication in public service, as he notices that “bosses only know what they don’t want, they don’t know what they want.”

There may be a tendency for middle managers to “second guess what the boss wants,” which he calls “a completely wrong way to make decisions.”

When a leader gets to make the final decision, a subordinate’s role is to ensure that the leader has all the facts and information needed to decide, he explains.

By not being afraid to “throw [new ideas] out there for discussion,” civil servants fulfill their duty to provide necessary context.

This is why Morgan argues that being too scared to speak up should be considered the “disciplinary offence of cowardice” as silence creates blind spots for the organisation.

Leader’s role to proactively create space

Within a large organisation like the government, there isn’t a lack of solutions, but the lack of psychological safety for officers to exchange and implement new ideas, Morgan notes.

To harness the innovation capabilities of the rich expertise within the government, public sector leaders must actively break the culture of silence that prevents officers from sharing their perspectives, he says.

The onus is on the leader to actively and safely invite feedback, he emphasises.

When leaders intentionally cultivate the soft skill elements of leadership, like fostering teamwork and psychological comfort, high-stakes situations become easier because every team member is aligned and confident in their role.

“My mission was to make sure that all the things that our officers don’t like would be done differently or better.

“The trouble is that people repeat the mistakes their bosses have made, and they don’t change.

“To be honest, when I saw my bosses do anything I didn’t like, I absolutely made sure I didn’t do the same thing myself as far as I could, or try to encourage people to tell me I should stop doing that,” he admits.

As Morgan progressed in his career with the police, he shares that he stopped worrying about what his bosses thought of him and his focus shifted to keeping his team happy and achieving what was best for the organisation.

While commanding teams during frequent protests, he also realises that he needed his team more than the other way round.

“If I'm not there, they can still do it. If they're not there, I can't do it,” he says.

This understanding clarified the dynamics of leadership, making it essential to prioritise his team's well-being.