Cleaning up Bengaluru: Embedding community ownership into the 11-km waterway

Oleh Si Ying Thian

Mod Foundation’s Amritha Ganapathy and Bhagyashri Kulkarni share how the creation of public infrastructure along the stormwater drain has incentivised residents to take care of the K100 waterway.

-1756123833337.jpg)

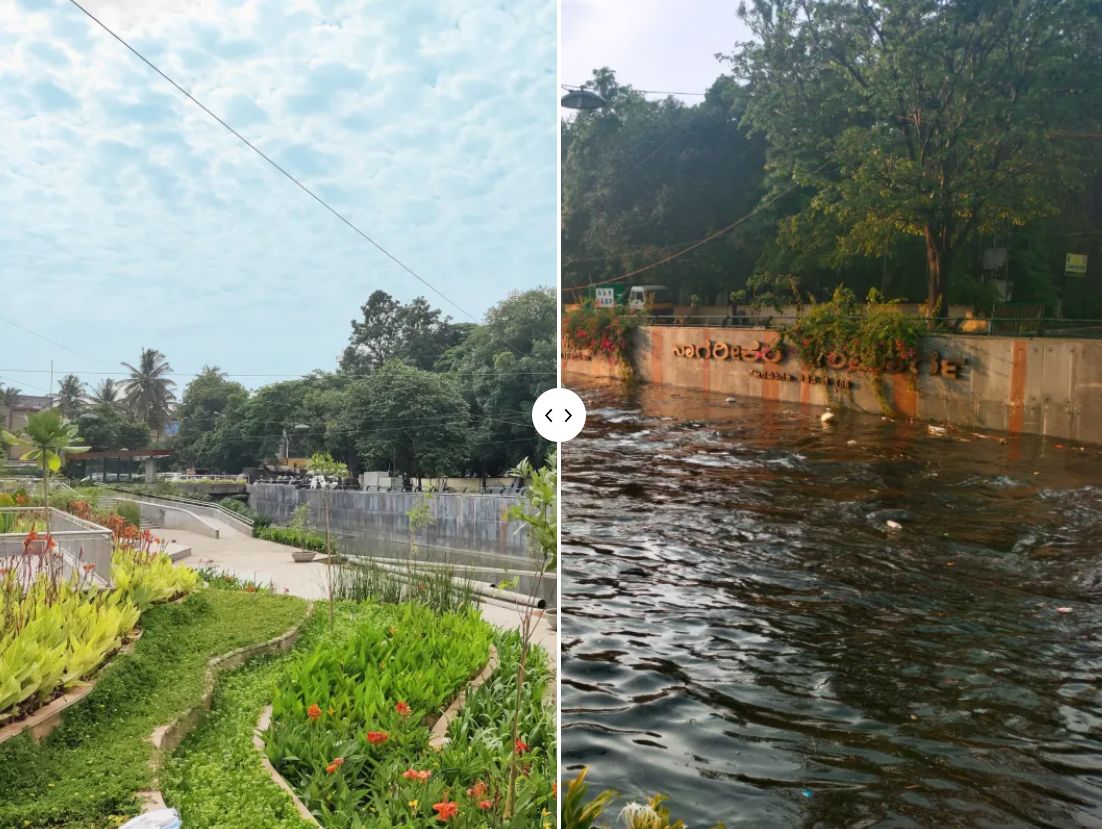

Before and after images of the K100 waterway project. Image: Mod Foundation

An 11-km stormwater drain in Bengaluru is standing the test of floods amidst the Indian city’s intense and frequent rainfall.

Since Mod Foundation initiated an intervention in 2021, the K100 waterway became the only stormwater drain in the city that did not flood in the 2022 rains, up till the most recently reported six hours of continuous rain last August.

-1756124127239.jpg)

Once shunned by residents of the city, the revamped waterway has since seen a higher footfall, rising property prices and more customer-facing businesses like ice-cream parlors moving in to take the place of scrap traders, according to a documentary film.

But this intervention was not limited to just cleaning up a drain, but weaving in aspects like whole-of-government collaboration and public infrastructure to maintain the current state of the waterway.

“By extending the drain as an everyday space (like an alternative mobility route), we wanted to cultivate relationship between the residents and the water in the city that doesn’t exist today and the residents had forgotten about,” says Mod Foundation’s Senior Urban Designer Amritha Ganapathy and Urban Design Associate Bhagyashri Kulkarni to GovInsider.

In the past when residents depended on the water body for agriculture needs, they explained that residents were incentivised to take care of the drain, but it became neglected over time with urbanisation and the lack of maintenance.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

Double whammy of trust and ownership

Build trust with results and the local community ownership of the public infrastructure will follow, Ganapathy notes.

“The continuous deterioration of the system and a corresponding lack of accountability has led to the lack of trust in local government,” she explains, admitting that the process has been a “slow building of trust.”

The first two and the half years of the initial phase of clearing silt and garbage from the drain has been a crucial step in building public trust, she notes.

“I think most people in this city are kind of used to the fact that projects start but they don’t see it beyond the first excitement... Even to show up almost every day [to clean up the drain] mattered more than anything else,” she explains.

Residents also witnessed firsthand how the waterway did not flood anymore with the rainfalls, and how a functional stormwater drain can be transformed into a vibrant waterfront.

In Bengaluru, stormwater drains typically function for about 60 to 90 days of rainfall a year, says Ganapathy.

To maximise use of these spaces and maintain the perception of a waterway throughout the year, the team has put in place sewage treatment plants to purify the wastewater.

A small amount of this treated water, about 15 to 20cm deep, will flow through the drains year-round, she explains.

Cosmetic change alone won’t cut it

According to the website, the project has created around five-km of walkable pathways connecting the city and 30-acres of public space that were reclaimed by the residents.

The five-km path provides another mobility option to ease daily communities and serve as a public space in very dense areas, essentially expanding the city’s everyday space, Ganapathy adds.

To further “bring public into the public infrastructure,” the team brought down the retaining walls for better visibility of the waterway, built additional bridges to improve access to the other side, more street lighting for safety, and added planters to enhance the greenery.

She observes that this has fostered a greater sense of community ownership among residents as they are now more likely to report littering to the authorities and even create vegetable gardens.

In fast-growing cities, public infrastructure can become a vital part of the local culture, she emphasises.

While new residents and migrant communities arrive in search of better economic opportunities, the shared use of these assets creates new meanings and relationships, transforming public infrastructure into a source of community, she adds.

Breaking silos

The team at Mod Foundation collaborated with 15 government agencies across disaster management, environmental protection, sewage and waste management, road infrastructure and more.

“This was the first time when everyone was in the same room and they were discussing how to solve problems together,” says Kulkarni, attributing this success to the political ownership by the state government of Karnataka.

Before, maintenance issues were handled by exchanging letters between different departments.

An identified problem can have many dependencies and by bringing together the different in a site inspection, it allows them to see how their work connects and collaborate on delivering a solution, says the Foundation’s project manager Raghu Rajagopal in the documentary.

Over time the team also picked up a key learning: The problem was not a lack of care from government officials, but rather a combination of being overwhelmed by their day-to-day work and a lack of awareness about specific issues, Kulkarni notes.

The project has created a new dialogue between the stakeholders, resulting in new awareness.

For example, she shares how connecting the technical aspects of the engineer’s job to the improved quality of life for residents can be a motivation for engineers.

When engineers saw the tangible impact of their work, such as a reduction in mosquitos and allowing people to walk outside safely, they become motivated to address the root causes.

Accountability mechanisms

The team identified community leaders particularly for solid waste management, Kulkarni shares.

They would capitalise on the existing work done by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the neighborhood and residents who live next to the drain to further raise awareness and incentivise efforts around monitoring, managing and sorting waste, and providing local insights.

As the team prepares for the official launch of the full 11-km waterway in the next few months, they are working to establish a clear framework with defined roles and responsibilities for future management of the waterway.

This ensures a rapid and effective response if an issue arises, such as taking specific steps during monsoon season like closing all the gates to handle rainfall, she shares.

The effort is connected to plans to establish an integrated command centre that will be managed by civil servants, which would allow them to use data to monitor and make decisions for all Bengaluru’s 840-km waterways when they are built.