How to prevent the next 1MDB - a global solution

By Joe Powell

Joe Powell suggests building a global public register incorporating information from all of the world’s major financial centres.

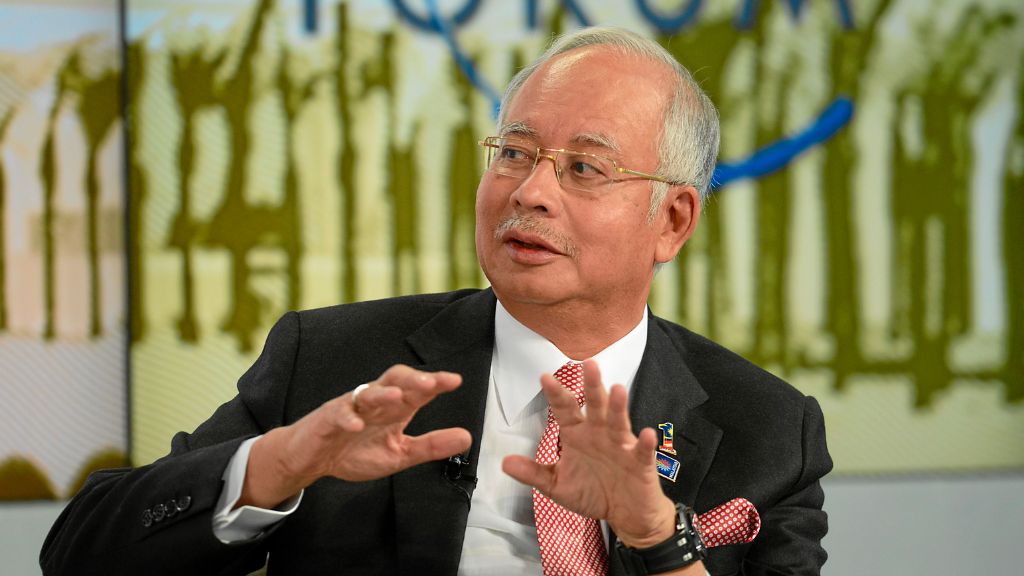

The allegation is that the funding for the blockbuster movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio was part of the US$4.5 billion siphoned off from 1MDB, Malaysia’s state-owned investment fund. The former Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was defeated in 2018 elections after 61 years of his party holding power in Malaysia, now faces over 40 charges of corruption.

Other key players such as former Goldman Sachs employee Tim Leissner have pleaded guilty to conspiracy to launder money, while Jho Low, the alleged orchestrator whose role is brilliantly documented in the book Billion Dollar Whale, remains on the run. Goldman Sachs itself has warned investors of significant legal liabilities and has set aside up to $1.8bn.

Policy lessons must be learned from the scandal. And more transparency and accountability should be injected into the global financial system that enabled theft on such a grand scale.

Uncovering corrupt networks

Tackling money laundering on this scale requires a raft of comprehensive measures from asset declaration, to open contracting in procurement and enforced freedom of information laws. A significant part of the answer is also to end the practice of anonymous companies.

Jho Low and others involved used shell companies based in tax havens, with anonymous or fraudulent company owners, to move around such large sums of money. In doing so, they avoided suspicion from regulators and the often toothless compliance departments in the banks.

These anonymous companies are also used to purchase assets like high-end property in which to launder the funds. A recent Canadian expert panel on money laundering found that in 2018 C$5.3bn of laundered money was used to buy real estate in the province of British Columbia alone and illicit cash inflated housing prices by 5%.

It has been ten years since I personally started working on this issue, and progress since then has been hard-fought, but promising. In 2013, at the Open Government Partnership (OGP) Summit in London, then Prime Minister David Cameron announced the UK would be the first country to have a publicly accessible register of company ownership.

Since it went live in 2016 it has been accessed an average of 20,000 times a day, and helped to contribute to the uncovering of corrupt networks used by governments, including the Azerbaijani Laundromat.

Efforts are now being made to go further. A promise to extend the registry to offshore property ownership made in 2018 needs to be fully implemented, and the UK’s Anti-Corruption Champion John Penrose MP has argued that trusts must also be incorporated into the register. British MPs continue to push for the UK’s overseas territories and crown dependencies, many of whom are home to large numbers of shell companies, to adopt the same reform.

A global standard

The challenge now is to build the global public register incorporating information from all of the world’s major financial centres and take this reform from an innovation to a new norm. 21 countries have committed to some degree of company ownership transparency in their biannual OGP action plans. The European Union’s Anti-Money Laundering Directive is also now kicking in, which requires public registers.

The sixth Global OGP Summit in Ottawa, 29-31 May, provides an opportunity for more OGP members to commit to this emerging global norm. OGP is supporting efforts of the UK government to convene a Leadership Group of countries committed to public and open registers of company beneficial ownership.

In Canada itself, there are signs that the federal government may pledge to step up its work with provincial governments to join the emerging global standard, amid increasing concern that the country is becoming a haven for “snow-washing” laundered money.

Keyword: interoperability

One of the main remaining concerns with public registers is privacy, so it is reassuring that a recent report found that public disclosure of beneficial ownership information can be made consistent with data protection legislation worldwide without violating individual privacy rights. Encouragingly, on recent trips to North Macedonia, Albania and New Zealand, I found each country doing their own assessment of whether to make this information public or not.

The disclosure should be done in interoperable open data formats to allow journalists and citizens to do the type of investigative work that ultimately exposed illegal activity in the Panama and Paradise Papers leaks. Indeed more needs to be invested into resourcing the people that can comb through these huge databases for suspicious activity.

Overall this progress may mean a tipping point is reachable, and it becomes unacceptable for countries to allow the opacity that fuels massive corruption, tax evasion and even terrorist financing.

Public registers of company ownership, while not on their own able to prevent the next billion dollar scandal, will make it significantly harder to conceal illicit activities across the world's financial system. The overdue end of anonymous companies will end the current financial getaway car of choice.

Joe Powell is the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the Open Government Partnership. He leads OGP’s global engagements, including working with the OGP Steering Committee, OGP Summits and linking OGP with other multilateral processes.