Blue carbon: Climate solution or policy illusion?

By Clare Lin

Attention is turning to the ocean not just as a victim of climate change, but as a potential solution to extreme weather, with blue carbon emerging as a promising pathway to net zero.

-1752730795892.jpg)

Evidence points to the fact that the oceans are at the receiving end of the brunt of climate change, but, at the same time, the answer to climate change may lie in the oceans themselves. Image: Canva

It’s hot, too hot.

Rise in global temperatures has accelerated in recent decades, and this has resulted in more natural disasters and a rise in global sea levels; in March, a NASA analysis revealed that sea levels rose faster than expected in 2024.

According to the IPCC 2023 report, the ocean absorbs 91 per cent of the heat generated by human activity.

This has a major negative impact on oceans: the rapid rise in temperature is responsible for worldwide coral bleaching, among other harmful effects.

Glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates. Sea levels are rising rapidly. The global ocean conveyor belt (oceanic circulation driven by variation in temperature and salinity) may also slow, affecting oceanic nutrient distribution.

Marine life on the whole is threatened.

Evidence points to the fact that the oceans are at the receiving end of the brunt of climate change, but, at the same time, the answer to climate change may lie in the oceans themselves.

While carbon sequestration is typically thought of to be done by terrestrial forests, current studies suggest that “blue carbon sinks” found primarily in coastal ecosystems can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at a rate of up to 10 times that of mature tropical forests.

It also stores three to five times more carbon per equivalent area than tropical rain forests.

Blue carbon may just be the key to slowing down global warming, but is it really that simple?

Who, what, why, blue carbon

The term “blue carbon” was first coined by Distinguished Professor of Marine Science at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia, Carlos M Duarte in the 2009 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report.

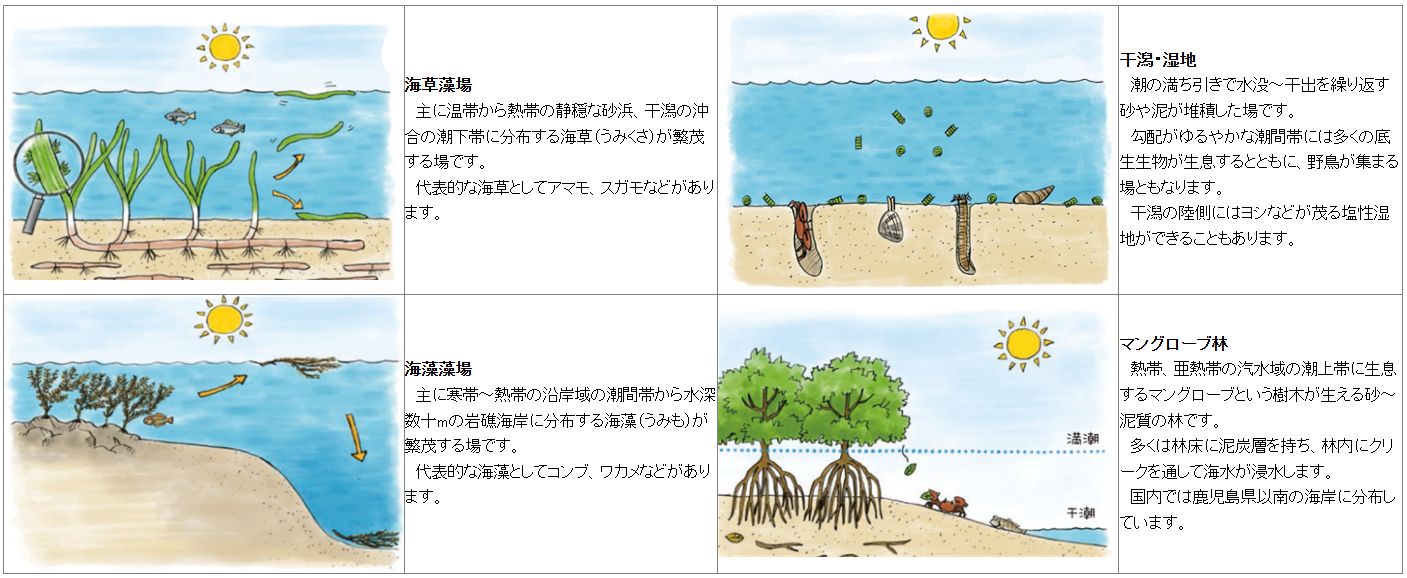

It refers to carbon captured and stored in marine and coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshes.

While these ecosystems cover only about 0.5 per cent of the ocean floor, they may account for more than 50 per cent of carbon buried in marine sediments.

Beyond carbon sequestration, these ecosystems are also vital in building resilience against climate change and preserving biodiversity in the ocean.

Mangroves and other coastal ecosystems dissipate the effect of waves, flooding and storm surges, protecting the coastline.

Yet, coastal blue carbon ecosystems are highly threatened, with an estimated 340,000 to 980,000 hectares being destroyed every year. It is estimated that up to 67 per cent of mangroves, at least 35 per cent of tidal marshes, and 29 per cent seagrass meadows have already been lost globally.

If this trend continues, a further 30-40 per cent of tidal marshes and seagrasses and nearly all unprotected mangroves could be lost in the next 100 years.

When degraded, these ecosystems become significant sources of carbon dioxide, and the land near the coast will be nearly defenseless against the sea.

The ocean’s wealth of biodiversity will also be threatened.

Diving into the web of the reef

Evidently, the blue carbon story extends into the depths of the ocean.

Unlike seagrass or mangroves that store carbon in their biomass, the colourful coral hiding beneath the sea operate slightly differently.

In an exclusive interview with GovInsider, National Parks Board (NParks)’s Group Director Karenne Tun shared how blue carbon was not an omnipotent resource despite the buzz around it.

According to Tun, corals recycle nutrients extremely fast, allowing them to be very productive ecosystems. Its living tissue is also very small, making its ability to sequester and store carbon quite unlike seagrass or mangroves.

“[Corals] actually support the other ecosystems.

“When you talk about ecosystems, without coral reefs, you don't get as much benefits to seagrass areas as well as mangroves. Just having a healthy coral reef supports these associated ecosystems. It adds to the whole blue carbon story because everything is interconnected,” explains Tun.

“It’s like a web, right?

“If you want mangroves to be a very productive blue carbon sink, you want seagrass to be very productive, then you need the web that keeps all of this together intact. And coral reefs are part of the web,” adds Tun.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

Blue carbon initiatives

While a 20 to 36 per cent loss of the blue carbon ecosystem in countries like Japan is believed to have already occurred, blue carbon projects have become focal to cutting carbon emissions and meeting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In April 2024, Japan became the first country to include carbon sequestered by seaweed in its national emissions report submitted to the United Nations.

However, according to a Professor of Marine Algal Ecology at Nagasaki University, Gregory Nishihara, it is impractical to capture carbon through seaweed alone.

To do so, Japan would have to use 10 per cent of its maritime exclusive economic zone, or approximately 433 million hectares of the ocean.

Moreover, according to the Japan Times, experts have found that blue carbon projects will need to be significantly expanded in order for it to contribute to Japan’s goal of net zero emissions by 2050.

While it is far from being a quick-fix solution, Japan has been investing heavily in efforts to promote blue carbon projects across the country.

Engaging stakeholders at all levels, the government-endorsed Japan Blue Economy Association (JBE) was also established in July 2020 to oversee the development of blue carbon credit standards and blue carbon projects.

Locally in Singapore, efforts to scale blue carbon initiatives have been underway since 2021 under the Marine Climate Change Science (MCCS) programme.

This was to enhance research efforts in mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs.

Funded by the MCCS programme, BlueCarbonSG is Singapore’s first blue carbon accounting framework, quantifying its potential to contribute to Singapore’s carbon reporting and climate change targets.

For a land-scarce nation, blue carbon ecosystems are significant carbon sinks - despite being almost 16 times smaller, mangroves in Singapore store 10 per cent of all the carbon stored in its secondary rainforests.

Ahead of the Third United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC3) held on June 10 in Nice, France, the ASEAN Blue Carbon and Finance Profiling (ABCF) Project has been launched in May signifying both a timely and strategic partnership between regions of high blue carbon potential.

The project, funded by the Government of Japan and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Indonesia, aims to enhance assessment of blue carbon stocks and integrate blue carbon strategies into national and regional developments across ASEAN and Timor Leste.

Is it really all that

Yet, within blue carbon scaling efforts lies something more insidious.

Although China appeared to have advanced its blue carbon policies, even approving a mangrove planting and carbon trading project in Zhanjiang, Guangdong in June 2021, questions have arisen regarding the accuracy of its carbon sequestration measurement methods.

Primarily, the concern has been whether shellfish carbon sequestration should be measured, as shellfish both absorbs and released carbon dioxide during their growth, and respiration and shell formation phases respectively.

Moreover, several reports have surfaced of blue carbon credits being used to offset environmental violations, raising concerns around accountability.

In a survey conducted by Dialogue Earth, offenders either purchased blue carbon credits to offset a portion of their charges of illegal fishing or destruction of marine ecology, or replanted mangroves elsewhere.

This abuse of blue carbon credits could potentially create a loophole, where it is used to evade the justice system.

While legislation on compensation of environmental damage appeared to be clear, it seems that the ruling on blue carbon trading in illegal fishing cases varied depending on jurisdiction.

Perhaps courts need to be more vigilant and consistent in their interpretation of rules on blue carbon trading, or even a presiding body to determine these standards in China.

Taking lessons from blue carbon pioneers, perhaps before jumping onto the blue carbon bandwagon, countries might want to consider the greater implications of adopting blue carbon in their national strategies.

There is certainly a lot of potential for blue carbon. However, addressing bottlenecks that involve blue carbon credits and blue carbon ecosystems early on may prove to be the foundation needed for the climate solutions to be truly effective.