Active citizenry in placemaking for citizen-centric and sustainable spaces

By Ming En Liew

In dense urban environments like Singapore and Hong Kong, space is a precious commodity. How can these spaces be designed to feel more like a home? GovInsider speaks with placemaking experts from both countries to find out.

The transformation of the O’Brien Road Footbridge (pictured above), was part of Design District Hong Kong, a placemaking project created to explore how design could improve liveability of a city. The bridge featured a botanical journey through the local seasons. Image: One Bite Design Studio

“The government doesn’t know everything,” says Ian Tan, Associate Director at a Hong Kong-based architectural firm specialising in placemaking, One Bite Design Studio. He was speaking about placemaking, defined by Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) as the “process of proactively managing a place to make it better.”

He goes on to explain that in the past, governments tended to adopt a top-down approach when it comes to public space design. The design process would be fairly standard, with a designer overseeing the project and ensuring that the space met basic safety requirements and provided a standard set of amenities.

“But placemaking goes beyond that,” Tan says. “The designer doesn’t feel that he or she is the only one working on a design. Rather, the community has a say on what features or what kind of design truly works for the community.”

In placemaking frameworks, the community can point out certain characteristics or special features in their own neighbourhood they would like to retain, or would like to see improvements on, he explains.

“When local communities, business operators and property owners take greater ownership of their neighbourhood or precincts, they are better able to implement ideas and solutions that meet their needs, and in turn inject greater vibrancy to their precincts,” observes Jason Chen, Director of the Place Management Department at the URA.

It is this belief in placemaking as a collaborative effort that guides placemaking efforts in both Hong Kong and Singapore. GovInsider sits down with both Chen and Tan to understand how placemaking is carried out in the two cities, and how it can enliven and enrich communities.

A community-led effort

When One Bite was tasked to redesign public toilets in Hong Kong, they first organised eight public engagement sessions to understand the needs of the users. In one such session, a wheelchair user highlighted to the team that she would have liked for public toilets in Hong Kong to include spaces for them to carry out tasks like putting on make-up, Tan shares. This was something the team had otherwise not thought of.

He explains that while the inclusive public toilet stalls were wide enough to accommodate a wheelchair, they lacked ledges along the walls which users could use to place their items down on. “Without these users telling us these anecdotes, we wouldn’t know that their needs are actually very simple,” Tan says. “But once you say it…the rest of the participants are able to empathise.”

This provided an opportunity for the stakeholders involved to consider what makes a toilet inclusive, he says.

Meanwhile in Singapore, the URA’s pilot Business Improvement District (BID) programme launched in 2017 aimed to encourage stakeholders to take greater ownership in enlivening their precincts, Chen says.

Chen highlights the Discover Tanjong Pagar pilot BID, which saw the Discover Tanjong Pagar team, made up of property owners and businesses in the area, partnering with stakeholders like residents, office workers, and early education practitioners to conceptualise and build an eco-playground. The team had sought to “beautify the community green space, and create something meaningful and sustainable to involve and bring the Tanjong Pagar Community together,” according to their website.

As such, the playground was built using upcycled wood from old felled trees, and incorporated elements of environmental education through dynamo bicycles which children could cycle to generate energy to power fairy lights, The Straits Times reported.

Inclusivity was another priority. The playground featured wood pieces teaching children sign language greetings and benches equipped with handlebars so that elderly visitors could easily use them, the Straits Times article stated. Since its launch in March this year, the playground has become a popular activity spot for residents and visitors alike, Chen says.

Enlivening ageing spaces

Placemaking needs to happen in context and recognise the needs of a place, according to Tan. In Hong Kong, for example, this could look like addressing the issue of “double ageing”, a phenomenon where the population is ageing alongside the city’s infrastructure.

“A lot of the public housing estates were built in the 60s and 70s,” Tan says. Since many of these facilities are not well-maintained, they tend to be underutilised, which further disincentivises proper maintenance, he explains.

One Bite Design Studio was therefore tasked to revitalise some of these public facilities. The objective was to bring people together and ensure that the service facilities catered to the community while tackling the double ageing issue, Tan says.

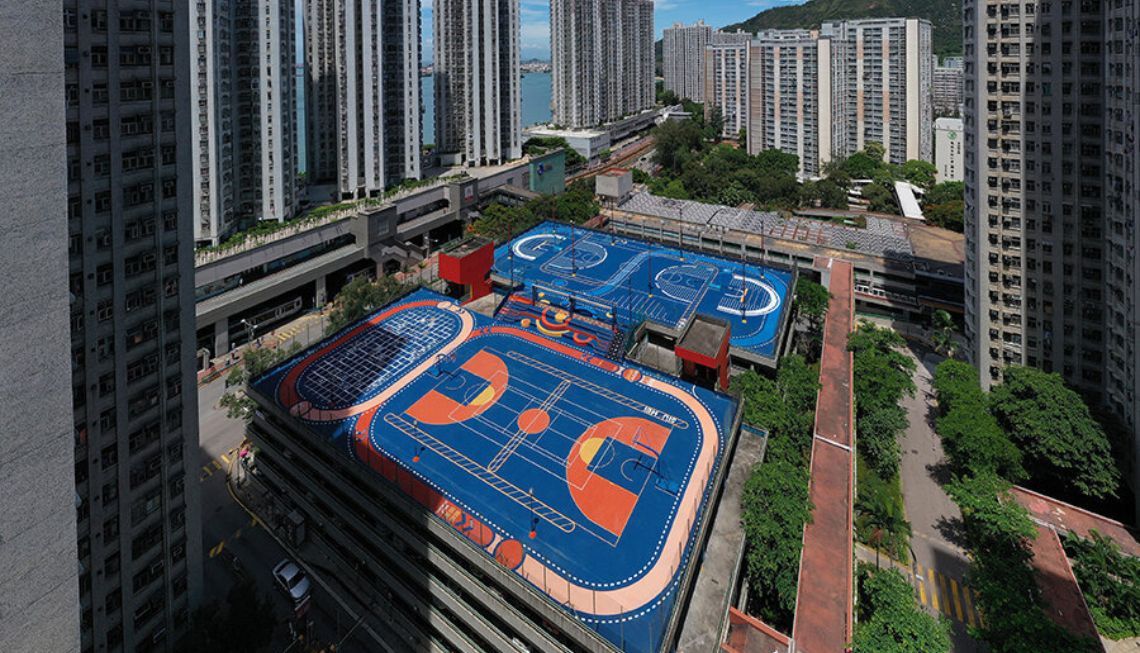

At the Kai Yip Estate, for instance, One Bite helped to revamp previously lacklustre basketball courts located on the rooftops of shopping malls and carparks.

They drew inspiration from Hong Kong’s neon lights, and painted the courts with colourful and eye-catching graphics. They also added new facilities, including running tracks, fitness training areas with equipment like battle ropes, as well as children-friendly facilities. Together, these features created a mixed-use space that caters not just to avid basketballers, but also families, children, and general fitness enthusiasts.

A similar project was carried out at the Siu Hei Court, located in the Tuen Mun area of Hong Kong. For this project, the team took inspiration from the name “Siu Hei”, which rhymes with “smile and laughter” in Cantonese, Tan explains. As such, they adopted bright colours with rounded typography to resemble smiles.

“We tried to imagine the low rooftop [of Siu Hei Court] as another facade,” Tan says. “When people stay high above, they can look down and see the motifs on the ground.”

By creating colourful facades, One Bite Design was also able to entice individuals living further away to flock to the area for photos. “A picture tells a thousand words, and also inspires people to take a thousand steps, to walk over there and visit a place,” Tan explains. Through social media platforms like Instagram, these pictures have helped to draw more visitors to the revitalised areas.

Sustainable placemaking

Singapore is faced with the challenge of catering to the wide-ranging needs of both a city and a country, Chen says. Placemaking in Singapore is therefore focused on the principles of long-term planning, to create a sustainable and integrated live-work-play environment, balanced against land needs, he adds.

One key priority, for instance, is sustainability. “Placemaking initiatives ought to imbue more eco-friendly practices that contribute to sustainable development, and improve the quality of life of the people,” Chen says.

One way Singapore does so is through events. While not a permanent fixture like the eco-playground or rooftop revitalisation projects, events are also an example of placemaking, Tan says. “Placemaking could exist in different forms, formats and lengths, but all with this objective of bringing the community together,” he adds.

For instance, the i Light Singapore festival was created to “encourage conversations about our lifestyles and consumption behaviour through inspiring light art installations made of environmentally-friendly materials,” Chen says.

According to the i Light website, the festival seeks to bring vibrancy to public places in the city centre, featuring light art installations by Singaporean and international artists, made with energy-saving lighting and environmentally-friendly materials.

One sculpture titled “Plastic Whale” sought to shed light on the plight of marine life amidst the rise of plastic pollution. Visitors walking through the exhibition will hear the struggling breaths of the whale as it tries to breathe amidst a sea of garbage, according to the installation’s description. Another sculpture combines artificial intelligence with weather and environmental data to create a light installation that functions both as a sensory experience, and a means of drawing attention to the climate crisis.

Lessons from two cities

While both Singapore and Hong Kong may have different priorities in their placemaking endeavours, Tan believes that there are learning points to be gleaned from both.

Singapore, he believes, has strong government support and many placemaking initiatives are coordinated at a higher level than in Hong Kong, Tan observes. The Place Management Department under the URA, for example, oversees placemaking efforts across the island nation’s central business district.

“When an agency takes the lead to coordinate, other supporting agencies will be more likely to come on board. This is very important to get the necessary permits, or to get the necessary approvals to run placemaking activities,” he says.

Meanwhile, where Hong Kong has an edge over Singapore is in holding space for public consultations. “Hong Kong has, for the last two decades, been very open to including the community voices or the public’s opinions in development projects,” Tan explains.

Public engagement is a component in many of Hong Kong’s place activation projects and public space designs, he says. “Because such a thing is put into the contract itself, it is easier for [placemakers] to suggest how to do things differently.”

Nevertheless, Tan highlights that there is still a need for more governmental support in the form of seed funding in both Singapore and Hong Kong. He hopes that governments in both locations will consider grants that can enable placemaking to become a permanent fixture in society.

To enable the community to better partake in placemaking efforts, the URA launched a book on placemaking last year, titled “How to Make a Great Place”. It features stories and lessons from individuals, communities, designers, architects and commercial stakeholders, providing useful tips and guidance for anyone interested in kickstarting placemaking efforts.

Ultimately, Tan hopes that placemaking will gain greater recognition in communities, with community members taking the lead to drive placemaking efforts forward as opposed to relying on established institutions like themselves.

“We are just a catalyst,” he says. “Once we have done our part, we hope to pass on the placemaking activities to members of the community. And I hope that that will be the aspiration for both Singapore and Hong Kong in time to come.”

Also read:

What does it take to create a society where tech and humans live harmoniously?