Clearer policies needed in the use of AI in the education sector

By Clare Lin

While there has been an exponential rise in efforts to increase AI and technology-based learning in schools, the recent NTU controversy opens a can of worms – where do we draw the line in AI use and need we draw the line?

-1751454373731.jpg)

NTU Hive. Image: Clare Lin.

The recent controversy regarding the use of artificial intelligence (AI) by students at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) has rekindled the debate on what constitutes fair use of AI and generative AI (GenAI) tools in the academic environment.

To understand the issue better there is a need to have a look at the bigger picture of how AI and GenAI is revolutionising the education sector in Singapore and elsewhere.

For teachers, this entails upskilling to meet the changing technological needs of the classroom, including AI specific training and technological competency training.

AI classes have also been introduced for students as early as primary and secondary school as part of the National AI Strategy 2.0 to expose students to GenAI.

It has become the norm for AI to be used both in, and outside the classroom, and even encouraged at times to increase efficiency.

However, with these changes comes a significant caveat - to what extent can AI be utilised, before it is considered excessive, disruptive or even fraudulent?

This is the central question behind the NTU controversy.

Embracing AI, but not really

Many institutes of higher learning, including NTU, have allowed the use of AI tools in assignments since 2023. Students, however, are expected to adhere to certain guidelines when using AI in their work.

According to a statement released by NTU on June 24, students are to declare the use of AI, and how it has been used.

The university also stated that some professors may prohibit the use of GenAI for certain assignments. This is to “assess students’ research skills, and their originality and independent thinking”.

Likewise, the National University of Singapore (NUS) has detailed guidelines on AI usage for academic work for both instructors and students.

What is the limit, really?

Some university modules, as with the Health Disease Outbreaks, and Politics class by Professor Sabrina Luk in the case of the NTU academic fraud controversy have a zero-use AI policy.

In this instance, three students received zero marks for an assignment in her class after they were found to have used GenAI in their assignments.

Since the controversy unfolded, one student was successful in having her grades reassessed, but the other two were not as fortunate.

Media reports suggest that the student whose grades were successfully reviewed was flagged for having used a citation sorter, which incorporated expired article links and for having three citation mistakes.

Citation sorters, or alphabetisers, are commonly used in academia, and NTU also advocated for using sorters such as Zotero in its Interdisciplinary Collaborative Core (ICC) modules, or school wide compulsory classes.

These sorters do not generally use GenAI in its processing, but programming languages such as Python instead.

Its use by the student was eventually deemed to be not considered GenAI when reviewed by an academic panel.

Moreover, while the school states that students must “ensure factual accuracy and cite all sources properly” when using AI, inaccuracies are not uncommon when dealing with a high volume of citations due to human error.

The presence of inaccuracies in citations therefore does not seem to be a good gauge for the authenticity of a piece of work.

Indeed, one can argue that the rules were set clearly and penalised appropriately: AI is not allowed to be used at all – it was falsely detected, and this incident and the ensuing damage was simply an unfortunate accident.

However, false positives for AI use in academia is not unprecedented – students that excel at writing have also been accused of using AI simply for short sentence structures or even punctuation such as em dashes – a common feature of AI-generated writing.

While professors use a variety of methods to check for AI use including AI itself to detect AI usage, this incident calls into question the veracity of AI checkers and the methods for detecting inappropriate AI use in the education sector.

Where then do we draw the line at what is considered “acceptable” AI use? Should students simply avoid writing in a way that may unintentionally incriminate them?

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

Lack of standardisation

In reality, the scope of what counts as acceptable AI usage remains dubious at best.

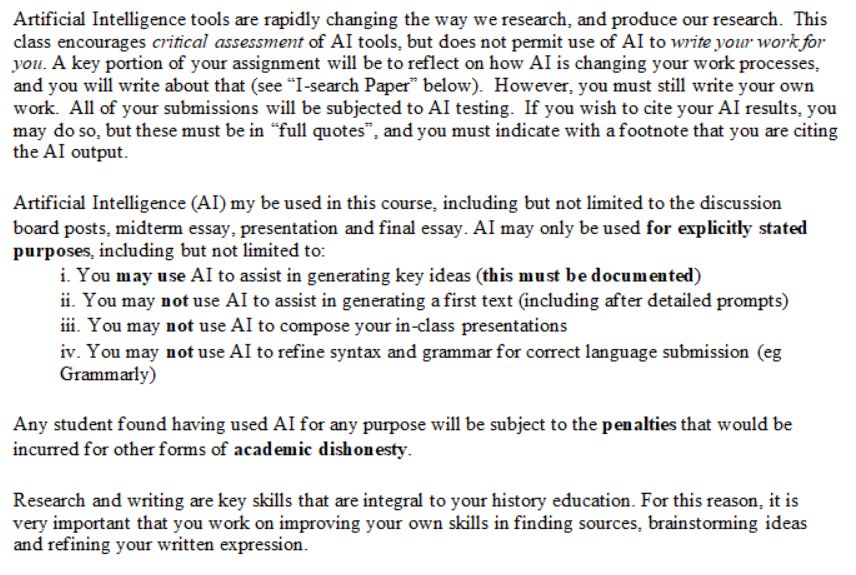

In universities like NTU, different modules have differing AI use policies. Different assignments in the same module even have different policies at times.

For instance, the NTU History module, HH3002 Science and Technology and Medicine in Modern East Asia (course syllabi pictured above) permitted the use of AI in the generation of ideas, but not in the refining of syntax and grammar using AI tools like Grammarly.

This module in fact encouraged the use of AI to generate ideas and assist in the retrieval of primary and secondary sources, so long as the detailed prompts used were submitted.

This is in great contrast to the guidelines in the class embroiled in controversy at the university. Yet, both modules are part of the overarching College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (CoHASS) in NTU, with a similar emphasis on writing and research.

Notably, according to one of the students involved in the controversy, Grammarly was not considered to be AI by the professor but is deemed as such in HH3002.

Evidently, there is a distinct lack of standardisation on policies for AI usage.

One cannot help but long for greater standardisation for what is considered AI.

The missing piece

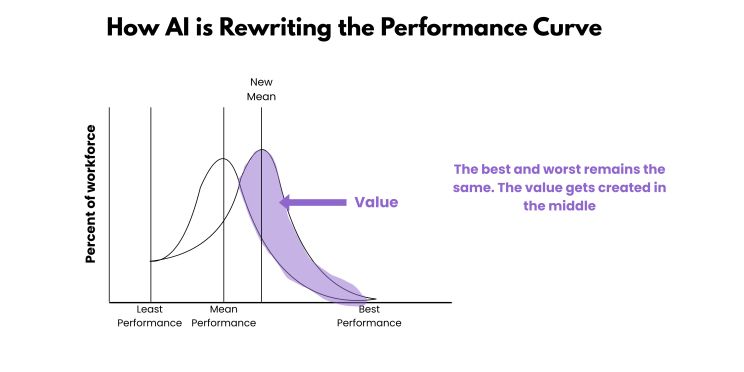

AI use cases such as language correction have become extremely commonplace among students, especially in higher education, raising the overall baseline for good writing.

While poorer grammar, spelling and vocabulary may have hampered some students in the past, AI has played a role in levelling the playing field.

According to a study conducted by Harvard Business School in conjunction with MIT and Wharton, AI is pushing the performance curve to the right, raising the “average” for the overall standard of work - more people are performing well.

For the average student at the odds of the bell curve, not using AI in their work means leaving them behind their peers.

The irony in having schools both pushing for AI adoption, but at the same time punishing students for simply engaging with AI, or what they may deem as AI is hard to ignore.

Ways forward

In an age where AI is no longer becoming a future possibility, but a present reality, the idea of limiting AI use to more accurately “assess students’ research skills, and their originality and independent thinking” as stated by NTU no longer seems as appropriate.

AI has taken root in everything, beyond the education sector.

Just last November, the use of AI-generated artwork by local bank DBS sparked outrage among local artists and as it was deemed to harm the livelihoods of artists.

The same issues arose when online users began flooding the internet with images of Studio Ghibli inspired AI-generated art.

And yet, whether we accept it or not, AI is the future. Students will use it whether it is permitted, and companies will use it so long as the profit is viable.

Schools should prepare students for the real world - a world that is vastly and rapidly changing.

Just as the course syllabi of the HH3002 NTU modules acknowledges, “Artificial Intelligence tools are constantly changing the ways we research and produce our research”.

It is ludicrous to impose the standards of an age where AI use was but a figment of our imagination on our present reality.

Likewise, technology has advanced rapidly, and society has now arrived at its fourth industrial revolution.

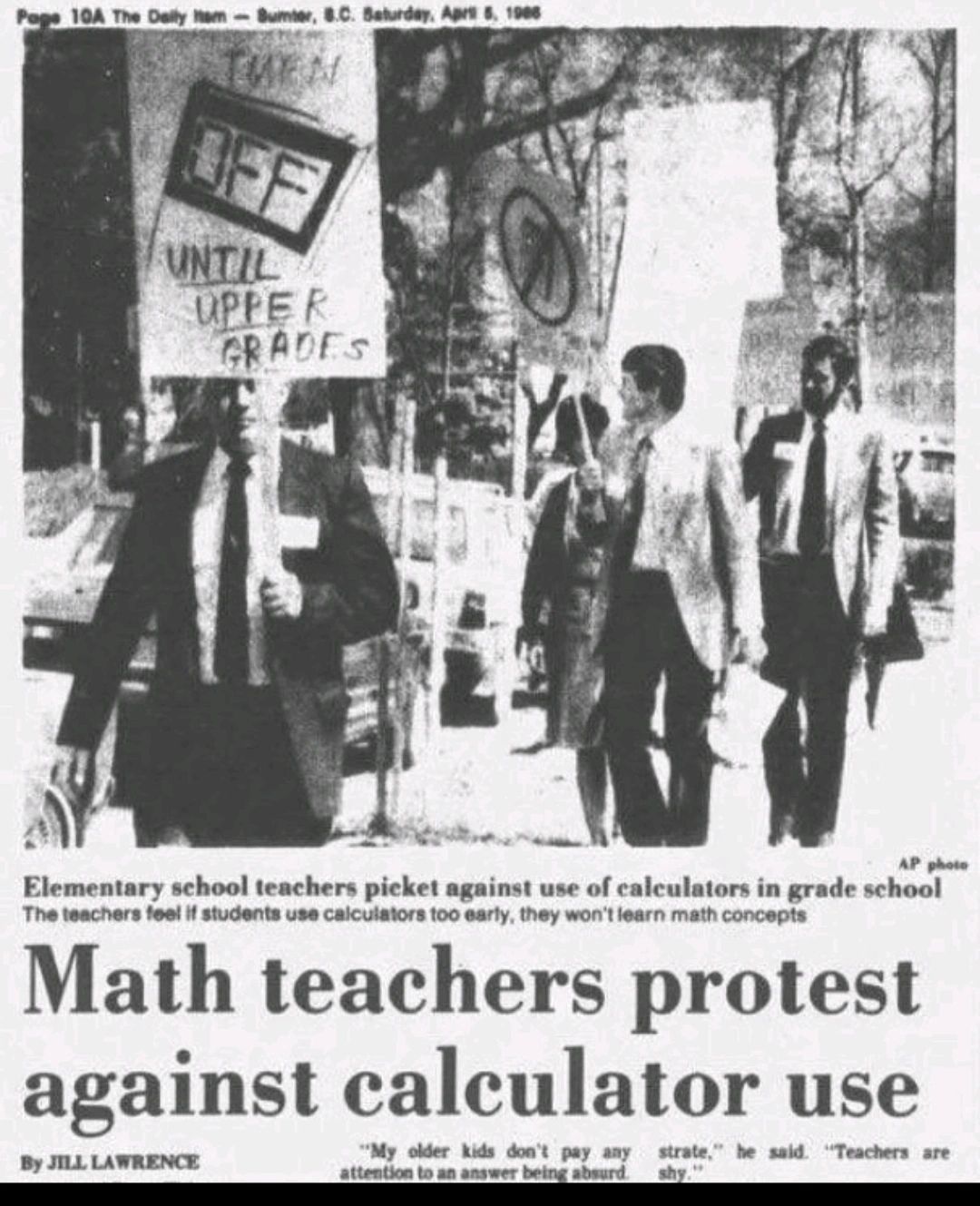

Back in 1980s, teachers in the US protested the use of calculators in classrooms. Today, calculators have become an integral part of mathematics and science education.

While there are indeed policies in place for approved calculators in Singapore’s education system, it has evolved to better balance efficiency with supporting the development of mathematical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Perhaps, instead of questioning whether AI should be allowed, or otherwise in education, the line of “acceptable” AI use needs to be revisited, and frequently to accommodate the rapid changes in AI.

Instead of selectively villainising AI, it is most apt for schools to embrace it and teach students how to use AI productively to complement their own intellect.