From communication to connection: learnings from tech-enabled public projects

By Ming TanAngeline Tong

This article draws from a presentation delivered at the GovInsider Live MY.AI Day held in Putrajaya, Malaysia on November 17, titled From Communication to Motivation: Connection at Scale, Learnings from Tech-Enabled Public Projects.

-1764042282592.jpg)

With the advent of big data, Internet of things (IoT), analytics, mobile apps and artificial intelligence (AI), the two-way relationship is no longer enough. Citizen engagement can now be dynamic, automated, predictive and co-created. Image: Canva.

The relationship between a government and its citizens is a dynamic and evolving social contract.

Using new technologies, governments can reach and interact with citizens directly. Citizen expectations are also shaped by these new technologies and what they experience from the services they use every day - banking, retail, travel, social media.

As a result, the nature of this relationship evolves. Tracing this evolution allows us to understand past strategies and to redefine success.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

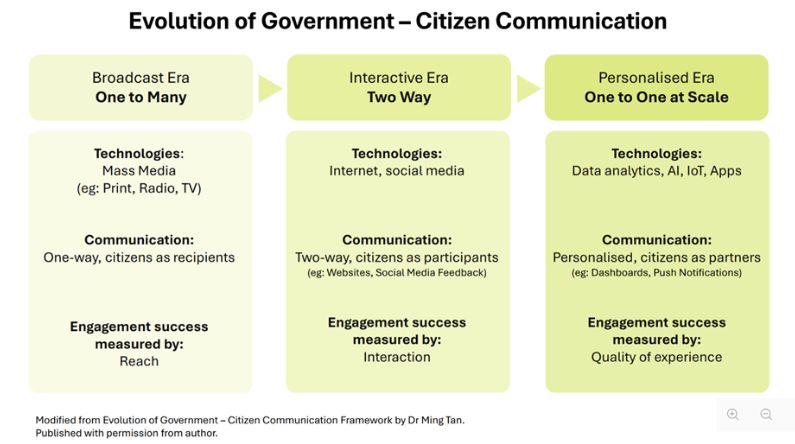

The broadcast era: the one-to-many model

Until well into the late 20th century, states disseminated single, uniform messages to the public through one-to-many mass media technologies. These included print, radio and broadcast television, each a set of significant technologies that revolutionised the way the public accessed and shared information.

Government communication was directed at citizens, aiming to inform, direct, and build a national consensus. Heads of states and governments determined how, what and when policy decisions were announced to the public.

Examples include the verbatim printing of important parliamentary speeches in newspapers, news programmes on radio and television, and public service announcements instructing citizens on everything from disaster response to public health.

The message was singular, authoritative, and consistent. Citizens will receive information in a coordinated way at the same time.

Public service delivery mirrored this one-to-many format.

Services were standardised with clear processes and workflows that generally functioned similarly for everyone, regardless of individual need or circumstance.

In this one-to-many era, citizen engagement prioritised reach and efficiency. What was the circulation of the newspaper that published the verbatim speech? How many people heard the radio address? What were the viewer numbers for the televised Budget speech?

The interactive era: two-way model

Just like how the rise of the internet, websites, and early social media platforms transformed the unidirectional relationship of the broadcast era, our relationship with government agencies similarly shifted.

Instead of waiting for office hours and physically going to archives and libraries, citizens could pull information on demand, starting with the government website.

Public records, service information and legislative records were now available around the clock. This new access increased convenience and transparency for citizens, journalists, and civil society.

Meanwhile, the ease of sharing information via email and social media platforms like X and Facebook provided real-time updates.

Every point of view has a platform, increasing diversity, but also condensing information into small packets tailored for immediate reaction.

Governments learnt to utilise these new channels for public communication, creating “always-on” information hubs. Public agencies segmented and targeted citizens with different messaging and channels, sometimes working with influencers and micro-influencers to connect with citizens.

The internet became a digital storefront for the government. Public agencies started adopting a platform approach, such as in the national Single Windows that enabled trade and transport stakeholders to provide information to multiple government agencies through one platform to meet import, export, and transit requirements efficiently.

As consumers, citizens expected the same reduced friction in administrative matters and public services as they experienced in everyday life.

Successful e-government initiatives enabled “self-service” processes such as paying taxes, licence renewal, registration for services or permit application.

These developments increased efficiency by reducing or eliminating the need for physical forms, standing in line or phone calls.

Commercial and public transactions soared during the pandemic as governments also adopted the platform approach to serve citizens with a user-centric manner.

Singapore's Life.gov.sg, for example, bundles services from multiple agencies around citizens’ life events, not the government's internal structure.

Through a “first contact resolution” philosophy of solving users’ problems at the first touchpoint, citizens no longer had to juggle processes across multiple agencies, or work through middlemen to navigate complex processes.

"Reach" ceased to be adequate metric of success; the goal was now engagement, action, interaction and satisfaction.

Public service success is measured by digital service adoption and task completion rates to measure whether and how citizens could easily and successfully use online channels for service delivery.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

The personalised era: one to one at scale

With the advent of big data, Internet of things (IoT), analytics, mobile apps and artificial intelligence (AI), the two-way relationship is no longer enough. Citizen engagement can now be dynamic, automated, predictive and co-created.

Citizens are expecting customised information and services. Personalised dashboards can show your tax status, your local services and your pending applications.

Push notifications from a government app, for example, provides proactive alerts, such as an approaching passport expiry, and a call to action: "Your passport expires in six months. Click here to begin your renewal."

Success of such initiatives prioritises outcomes over inputs, experience over usage, usefulness and ease over completion.

Relevant metrics might include a Citizen Effort Score, adapted from Customer Effort Score used by businesses to measure how easily customers purchase, obtain support and interact with the company. A Citizen Effort Score might seek to measure, for example, how easy it was for an issue to be resolved, regardless of online or offline channel.

When designed and executed effectively, the outcome extends beyond satisfaction to drive public trust and motivation.

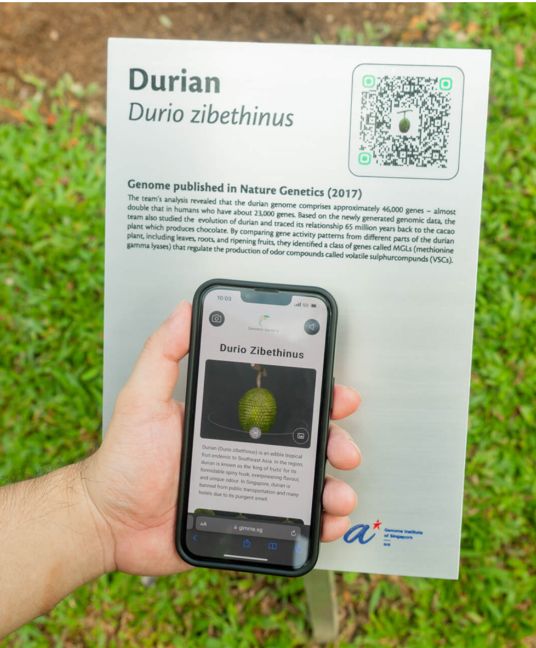

For instance, experiential consultancy HOL partnered with Singapore’s SingHealth Duke-NUS Institute of Biodiversity Medicine (BD-MED) to deliver personalisation at scale for the world’s first Genomic Garden, by bridging the physical and digital realms with distinct experiences that met specific user motivations.

For the curious, an 'edutainment' layer reframed complex science as play, using gamification and personalisation strategies to lower cognitive barriers and encourage social sharing.

For donors and partners, a 'demonstration' layer featured tiered data and a personalised AR welcome from the Director to communicate the institute’s innovative vision.

Through resonant connection with the user, the solution did not just inform; it catalysed support for the future. This strategy contributed to a 300 per cent acceleration in core research and was published in Cell Genomics as a model for the scientific community while being featured by the Asian Development Bank as a key technology innovation.

The mindset shift

The relationship between government and citizen will continue to evolve.

Generative and agentic AI holds the potential for automated, personalised and helpful assistance.

Moreover, open government data and infrastructure such as Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) empower citizens, non-profits, and the private sector to build services to meet citizen needs.

In the property sector, for example, many commercial real estate websites already draw on open official data on transaction volumes and value to inform their users on market trends.

With the government acting as the single source of truth by providing its data for an innovative public-private ecosystem, this next shift heralds the potential for the relationship between government and citizen to evolve from one of communication to connection to co-creation of public value, such as the example of genomic research.

Achieving this, however, is more than a technical challenge.

Institutionally, governments need to build new capabilities in data governance for interoperability and artificial intelligence governance to manage open innovation securely.

Most importantly, we need a mindset shift to understand what resonates and motivates citizens to be part of the solution, with government moving from a platform approach to becoming enablers of many potential platforms, products and services for public benefit.

Tan is a Senior Fellow and Founding Executive Director, Tech for Good Institute while Tong, is Co-founder and Chief Experience Officer, HOL.