GovMesh Digest: India’s digitalisation journey started with land records

By Amit Roy Choudhury

Open source has been the driving force behind all government programmes, from digital identity and government software to open marketplaces and knowledge sharing.

India’s journey in developing its digital public infrastructure started with the digitalisation of land records in the 1980s. Image: Canva.

India's story is one of those featured in the GovMesh Digest special report. You can find the individual stories on the other participating governments at GovMesh 2.0 here.

In the digital public infrastructure (DPI) space, India has often been held up as a shining example of what was possible with planned digitalisation to uplift the lives of entire populations.

The India Stack, which was central to India’s digitalisation drive, has widened access to financial services in an economy where retail transactions have traditionally been heavily cash-based, according to the World Bank.

The World Bank report, like other studies, noted that India’s DPI journey took off during and immediately after the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the pandemic and the associated restrictions gave a significant boost to India’s digitalisation journey, what is less known is that the country took its first baby steps in this direction as far back as the 1980s.

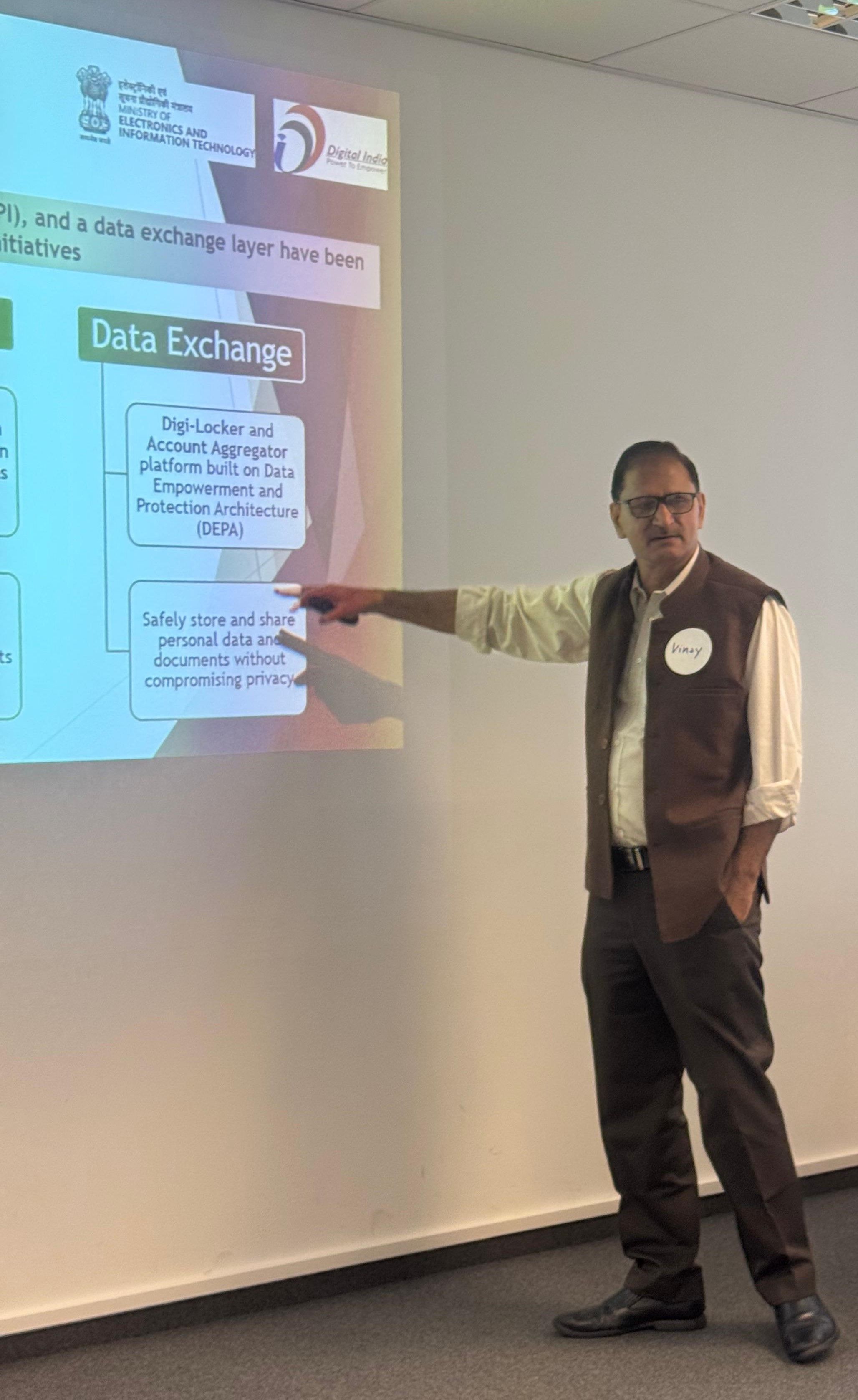

Giving a talk titled: The power of openness: Policies as an enabler for India's open-source digital government, at Berlin in early June at the GovMesh 2.0 event, Vinay Thakur, who was one of India’s foremost experts in DPI, said the country first started with the digitalisation of land records in the late 1980s.

GovMesh, co-organised by GovInsider and interweave.gov, is a closed-door roundtable discussion that convenes a small group of governments to discuss selected topics around digital government.

Building on early successes

Thakur, who is the Bhaskaracharya Institute for Space Applications and Geoinformatics (BISAG-N)’s Special Director-General, noted that India’s initial efforts to digitalise land records faced problems ranging from the vast scale of data, the need to accommodate 22 official languages, and the lack of suitable digital standards for Indian scripts.

The breakthrough came with the success of projects like the Indian state of Karnataka's Bhoomi, which mandated digital-only land records and enforced compliance through legislation.

This set a precedent for other states and showed the importance of strong policy and documentation, he noted.

Building on these early successes, India launched the National e-Governance Plan (NeGP) in the mid-2000s, “aiming to extend digital infrastructure to all districts and sub-districts, and to provide citizen services across 27 sectors, including land records, banking, and postal services”, Thakur said.

Initiatives such as the Common Service Centres have brought digital services to rural areas, while the adoption of open data and open-source policies has fostered innovation and collaboration among government, startups, and the community, he noted.

Thakur added that a key tenet of the Indian government’s use of IT resources was the preference for open-source software.

“Departments were required to evaluate open-source alternatives and may only opt for closed source solutions if they provide a clear justification for doing so,” Thakur, who as the former Managing Director of India’s National Informatics Centre Inc (NICSI) under the country’s Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology (MeitY), was part of the policy making team, said.

Supporting this open-source initiative was the country’s OpenForge policy, he added.

Managed by India’s National e-Governance Division (NeGD), OpenForge was a platform for collaboration between government departments, private organisations, citizens, and developers to create innovative e-governance solutions.

Avoiding vendor lock-in

On the preference for open-source, Thakur explained that the government believed that this “not only reduced costs and avoided vendor lock-in but also encouraged innovation and collaboration across government agencies and with the broader technology community”.

The policy has led to widespread adoption of open-source platforms, with most government digital solutions now built on open technologies, he added.

He noted that the government has established comprehensive standards for both technology and domain-specific applications tailored to Indian conditions but aligned with international best practices, such as ISO.

Thakur said the policy mandated robust cybersecurity measures, including a national cybersecurity policy, and the use of official government email addresses (gov.in) for all official communication.

The launch of Digital India

Going to the next stage of its digitalisation journey to “transform the country into a digitally empowered and knowledge economy”, the government launched Digital India in 2014.

Thakur observed that Digital India “encompassed a wide range of projects, from the digitisation of land records and the creation of digital identities to the development of platforms for health, education, and agriculture”.

The flagship project under Digital India was the real-time payment system Unified Payment Interface (UPI) that enabled instant money transfers between bank accounts through mobile devices.

“With over 500 banks connected to the platform, UPI has revolutionised the way Indians conduct financial transactions, making payments fast, secure, and free of charge for users,” Thakur noted.

According to media reports, UPI, available in seven countries at present, has overtaken Visa’s global number of daily transactions within nine years of its launch.

National public procurement portal

Another major initiative has been the establishment of the Government e-Marketplace (GeM) to streamline the government’s procurement processes.

Designed as an online marketplace, GeM has created a digital platform for government procurement which was open to all, Thakur said, highlighting how it cut the need for paperwork like tender documents and ensured competitive pricing through real-time price discovery and standardised specifications.

Another initiative shared by Thakur was India’s digital infrastructure for knowledge sharing.

He said, “the vision behind this infrastructure was to democratise access to information, learning resources, and best practices across sectors, empowering citizens, educators, and policymakers alike.”

Thakur said the education sector exemplified the success of India’s digital infrastructure for knowledge sharing, with “platforms like DIKSHA (Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing) leading the way”.

DIKSHA provided teachers, students, and administrators with access to a vast repository of digital textbooks, lesson plans, and interactive learning materials.

The platform supports content in 22 Indian languages and is designed to be accessible on a range of devices, including low-cost smartphones.

He noted that artificial intelligence (AI) has been integrated to personalise learning experiences and provide intelligent support, while open data policies ensure that government-generated knowledge resources are freely available for reuse and value addition

Beyond education, India’s digital knowledge-sharing infrastructure has been extended to sectors such as health, agriculture, and governance, enabling the sharing of best practices, research findings, and policy guidelines, Thakur added.