How Singapore is designing more accessible digital services

By Sol Gonzalez

GovTech Singapore has launched a new website with assessment tools for developers, that help to empower persons with disabilities to navigate the digital world independently and confidently.

-1754020776222.jpg)

Minister for Digital Development and Information, Josephine Teo, was the guest of honour at GovTech Singapore's Inclusive Design Week 2025. The event gathered advocates for inclusive digital design practices in the public and private sectors and members of the PwD community. Image: GovTech Singapore.

Imagine opening a government website to fill up a form, and being presented with a whole block of text, accompanied by images that are purportedly there to guide you to the correct page for the service you need. The whole experience leaves you confused.

For persons with disabilities (PwDs) who rely on assistive technologies like screen readers and eye trackers, this is often the experience when navigating and interacting with websites.

“It could be intuitive to you if you’re seeing it holistically [with text, buttons, and pictures], but to the screen reader user, they only see one thing at a time,” says GovTech Singapore’s Principal UX Designer of Government Digital Products, Joy Ng, to GovInsider at a media conference.

Ng is part of the team behind the launch of a new website, A11y Playground, at GovTech’s Inclusive Design Week 2025.

The website helps designers, developers, and digital service owners to ensure their products meet accessibility standards.

A11y Playground includes a technical checklist to assess how accessible a digital product is, real-life stories of PwDs, and interactive games that raise awareness on the challenges that PwDs face when navigating less accessible digital services.

The website’s aim is to put accessibility into practice and at the forefront of design and development processes.

This was one of the main points shared at the Inclusive Design Week event held on July 29 at the Enabling Village in Singapore.

The conversations at the event prompted attendees to re-evaluate the accessibility of common processes like OTP authentication and QR codes, incorporating perspectives from the PwD community to foster more inclusive designs.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

Who is responsible for accessibility?

“We can’t have just one role pushing for accessibility,” Ng shares.

She notes that the website is built to empower everyone involved in creating digital services, including product managers and software developers.

This included practitioners and designers who are PwDs where the website was built in accordance with the resources provided.

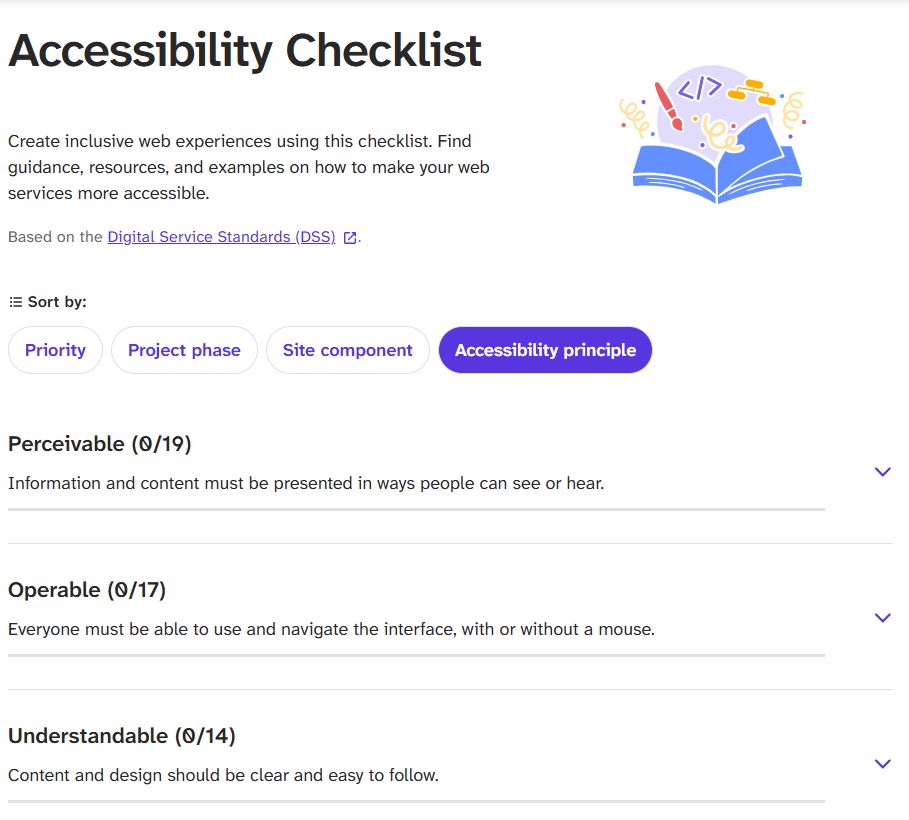

Ng explains that the accessibility checklist feature draws on the Singapore government’s Digital Service Standard (DSS), with the GovTech team ensuring its items are actionable for developers, Ng adds.

Users can sort the checklist by different criteria, including priority items like minimum contrast for text, which makes content easier to read, particularly for people with low vision or colour blindness.

The checklist can also be sorted by site components such as consistent page structures and error prevention, which provides a starting point to create an inclusive website.

Ng adds that the website project launched after a three-month development period.

Work began in April with brainstorming and content gathering, followed by coding in June.

Integrating feedback

Ng says that the goal following the launch of A11y Playground has been to promote the idea of “ensuring that your product is accessible from day one”.

This meant “shift left” by writing accessible code from the start.

Shift left is a software development principle that involves moving quality assurance and other development practices to earlier stages in the software development lifecycle (SDLC).

One way in which the team has adopted this approach in the design process of different products has been by integrating feedback from users and PwDs in three phases.

“[The] first phase comes from user feedback at the start. The next phase is where we co-create with users and the last stage is where things have already been built, so the feedback comes from the prototype,” says Ng.

The second phase involving co-creation adds value to cases where there’s no prototype or code in place yet, she explained: “We ask [users] ‘what would you like to see? What would you want to envision?’, and we run a lot of envisioning workshops to generate ideas together.”

“For all the users, we don’t see them differently. It’s just their needs might be different,” Ng explains, noting that placing accessibility at the forefront creates products that are better designed for everyone.

Everyone has different needs

At the event Jasmine Yau shared her experience navigating websites with the gaze of her eyes instead of her hands and a mouse due to spinal muscular dystrophy.

According to Yau, navigating websites with unclear visual cues (such as unlabelled buttons or complex interfaces) is confusing and frustrating, especially when some platforms have not been designed to respond well to her gaze.

One example she shared was navigating services that prompted an OTP (one-time password) authentication, a process that has increasingly become common in recent years as two-factor authentication protocols kick in.

Yau noted that this extra layer of security may not have been designed with accessibility by PwDs in mind.

OTP authentication requires users to verify their identity by inputting a temporary code sent via SMS, email or an app, often within seconds. But for individuals who rely on screen readers or eye gaze navigation, this process becomes frustrating and repetitive as it often requires more time.

While OTPs are often referred to as quick and efficient ways of authentication, this may be based on ableist assumptions as not everyone navigates websites with the same speed.

Overcoming these assumptions and embedding accessibility as a core consideration in developing digital services was one of the key messages from the conversations at the event.