In the heat of the moment: How cities can adopt sustainable urban cooling

By Woo Hoi Yuet

With global warming in full swing, the heat is here to stay. Climate and cooling experts chime in on how cities can adopt sustainable urban solutions to cool the heat.

In Singapore, flats are designed with natural ventilation in mind. Open spaces at the ground floor of apartment buildings allow for increased air flow, which makes the space breezier. Image: Canva

These unprecedented temperatures are not an anomaly. A study revealed that human-induced climate change has made the deadly 2022 heatwaves in South Asia 30 times more likely. As the climate crisis remains unresolved, the rising heat is only going to become the new normal.

But cooling must not continue on a business-as-usual basis, says Lily Riahi, coordinator of the Cool Coalition. Established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) – which focuses on global environment issues – Cool Coalition aims to bring governments, cities, and civil society together to advance climate-friendly cooling.

Oftentimes, when the temperature rises, the first instinct is to crank up the air conditioner, Riahi says. But “air conditioners are a double burden when it comes to climate change”. Not only do they contain hydrofluorocarbons, a harmful greenhouse gas, but they also consume a lot of energy, she explains.

According to the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program, conventional cooling accounts for over seven per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The World Bank estimates that if left unchecked, these emissions are expected to double by 2030 and triple by 2100.

“The hotter the planet gets, the more energy we use to cool ourselves and the more we emit,” Riahi explains. “And so the downward spiral continues”. To prevent this from spiralling out of control, experts today are working on more sustainable forms of cooling for cities around the world.

Cities in the heat

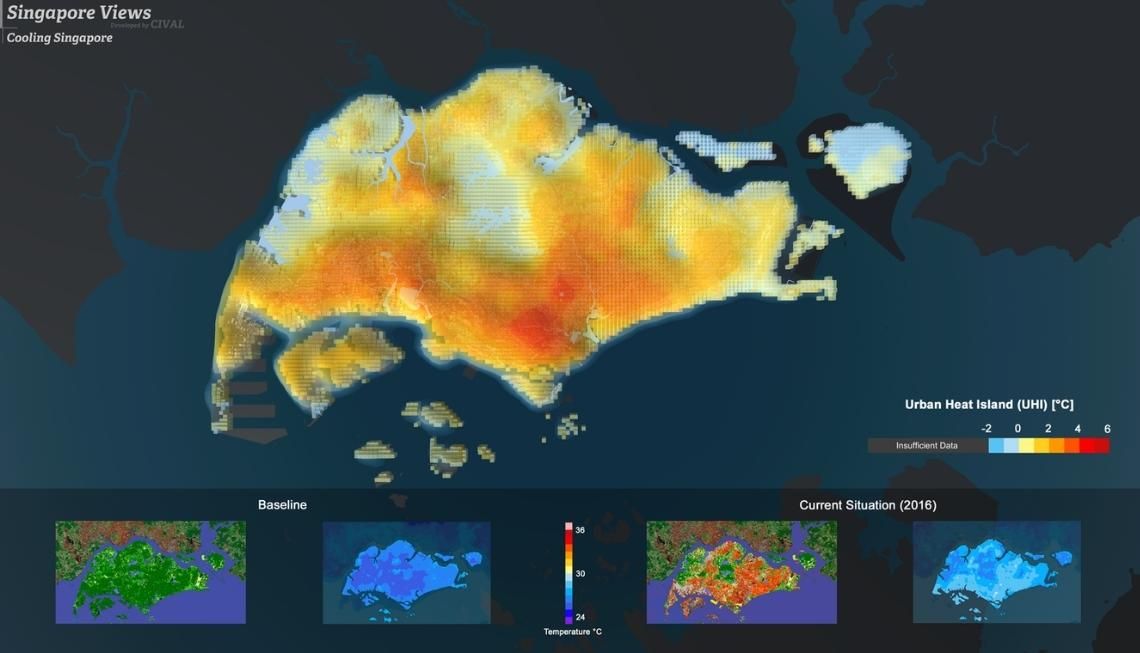

The urban heat phenomenon, where cities experience higher temperatures than their surrounding environments, is a pressing concern for urban areas around the world, says Ander Zozaya, project manager of Cooling Singapore – a project launched by research hub Singapore-ETH Centre to address the heating challenge in the island nation.

UNEP warns that by the end of the century, cities can experience an increase in temperature of up to 4°C if emissions remain high. Even a 1.5°C warming can cause 2.3 billion people to become vulnerable to serious heat waves.

The heat crisis is also a major source of social inequality as the vulnerable and poor are disproportionately affected, says Riahi. For instance, workers in low-skilled sectors like construction who frequently work outdoors are more vulnerable to rising temperatures than office workers in air-conditioned buildings. A study by the American Geophysical Union revealed that low-income populations have a 40 per cent higher exposure to heat waves due to their location and lack of heat adaptations.

But urban heating is tough to tackle. Challenges include gaps in urban planning and enforcing building standards, limited awareness and capacity to develop urban cooling projects and a lack of finance for cooling interventions, says Huong Ta, Senior Program Officer at the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) Viet Nam. The GGGI is an intergovernmental organisation created to support and promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth in developing countries and emerging economies.

Digital twins for better urban planning

In Singapore, urban heat is not a new consideration for city leaders and planners. “Void decks in our HDB flats help enhance natural ventilation in our housing estates,” says Zozaya. The open spaces at the ground floor of the flats allow for increased air flow, making the place breezier.

In line with Singapore’s national green plan, Cooling Singapore is currently developing a Digital Urban Climate Twin (DUCT) that simulates Singapore’s urban climate and runs “what-if scenarios” related to cooling.

The digital twin will be a useful policymaking tool, says Zhang Weijie, Divisional Director of the Energy and Climate Policy Division, Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment. The simulations allow government agencies to assess the effectiveness of various urban heat island mitigation policies before implementing them, he adds.

DUCT can help city planners analyse how future developments will impact wind corridors in the city, for example. Zozaya shares that the tool can identify areas with high or low potential for wind, allowing planners to conserve such areas when needed.

Other tools within DUCT include analyses of how greenery and parks impact the temperature of surrounding neighbourhoods, and the impact of building energy efficiency on heat generated by human activities, he adds. Insights from these simulations can be incorporated into urban planning and drive effective cooling strategies.

National frameworks

Although access to cooling has been acknowledged nationally as a public health imperative, “greater municipal intervention on cooling and extreme heat is a crucial but underdeveloped element in Viet Nam’s policy frameworks”, Ta says.

Many countries are therefore developing national cooling action plans (NCAPs), a framework that can catalyse action on cooling. NCAPs set a baseline to meet future cooling demand sustainably, coordinate policies across the country, and gather stakeholders required for their implementation, Riahi explains.

India, for instance, was among the first countries to develop an NCAP in May 2019. It provides a 20-year outlook on India’s cooling demand across sectors like transportation and buildings, and outlines strategies that promote sustainable cooling practices across the nation. Examples include phasing down pollutive refrigerants, developing alternative cooling technologies, and building cool roofs for affordable housing projects.

Riahi says that India’s NCAP has become a reference for the transformative potential of such plans. Over 30 countries, including Viet Nam, have adopted or are developing NCAPs. Meanwhile, organisations like the Cool Coalition and GGGI have been working with governments to develop clean cooling initiatives to help them achieve these NCAPs.

“UNEP is working with national and local governments to devise creative solutions to spare people from extreme heat by leveraging the resources and know-how of local communities,” Riahi adds. For instance, UNEP released a sustainable cooling handbook, featuring 80 local case studies, to guide cities in solving the heat challenge.

In India, where only nine per cent of households have air conditioning, UNEP is working with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs to establish a national programme that implements accessible and inclusive cooling solutions in cities. This involves planting more trees, building green infrastructure, and establishing cooling centers in 100 cities within the nation.

GGGI is also collaborating with UNEP and Viet Nam’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment on a sustainable urban cooling project, Ta says. It aims to develop urban cooling action plans for three pilot cities, unlock financial instruments to fund cooling solutions, and improve urban design and district cooling solutions.

UNEP and GGGI are mapping extreme heat in two Viet Nam cities to identify hotspots and solutions to reduce heat, Riahi adds. They will also aid the government in updating national planning guidelines and establishing a fund to help cash-strapped municipalities develop sustainable cooling strategies.

“The project will support replication in other cities in Viet Nam to seize the opportunity of efficient and climate-friendly cooling,” says Ta.

Urban strategies

Cities need a whole-system approach toward sustainable urban cooling, notes Ta.

The strategy consists of three steps: The first is reducing heat at the urban scale. This can be done through heat-resilient planning and infrastructure at the scale of the city, such as by incorporating greenery and cool surfaces. For example, Singapore has rolled out green-roofed bus stops, which preliminary studies found could help lower ambient temperatures by around 2°C.

These passive strategies help to reduce the demand for active cooling, Riahi says. Cities can also build more urban forests and parks, which can be up to 7°C cooler than other parts of the city, she adds.

Passive cooling provides cost savings as well. When cities do not have to constantly ramp up active cooling solutions such as air conditioning, they can save up to US$570 billion on power generation.

The second step is to reduce the need for cooling in buildings. For instance, buildings can choose to use materials that minimise heat gain. Building design can also aim to increase natural ventilation and provide more shading.

The third step is to ensure that existing cooling needs in buildings can be met sustainably. Leveraging efficient cooling technologies allow buildings to decrease energy use while still providing the necessary amount of cooling, explains Ta.

“Asia is home to some of the most heat-stressed countries globally, and the most energy consuming,” says Riahi. As urbanisation continues apace, the need for sustainable cooling solutions will only increase. By adopting national cooling action plans, urban strategies, and efficient technology, cities can help protect their residents from extreme heat.

(28 October 2022/Editor's Note: This article has been edited to include comments from Singapore's Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment on the Cooling Singapore initiative.)