GovMesh Digest: How empathy became a digital government superpower in Montenegro and the US

By Luke Cavanaugh

Tamara Srzentic shares how psychological safety and active listening transformed digital cultures in California, US, and her home country.

Montenegro's story is one of those featured in the GovMesh Digest special report. Image: GovInsider

Montenegro’s story is one of those featured in the GovMesh Digest special report. You can find the individual stories on the other participating governments at GovMesh 1.0 here.

Tamara Srzentic’s story is one of humanising government through digitisation, first in California and then in Montenegro.

The self-styled “bureaucracy hacker” began her presentation at GovMesh with a rousing message – “technology has not changed our shared mission of service, it has simply given us new tools”.

For Srzentic, the impetus for her major government positions came about through two crises: the failure of the healthcare.gov website under Obama, and the Covid-19 pandemic in Montenegro.

Empathy: a digital government superpower

The story of the Obamacare’s healthcare-gov website failure frames many a digital government handbook.

Some 500 vendor organisations worked on the website together, creating a US$10 billion-dollar IT project which dramatically failed and crashed upon launch.

Not letting a crisis go to waste, the administration’s response has become something of a digital government legend. The US Digital Services was founded to put things right – to re-engineer the website and re-orchestrate the US government’s broader digital ecosystem.

The US Digital Service has since become a model for similar institutions at a state level, including the one in California that Srzentic joined.

There, she too used a sense of crisis to “quickly gain political capital, space and permissions to reshuffle the old rules and structures” through the lens of human-centred design.

To subscribe to the GovInsider bulletin, click here.

It is empathy, not digital talent, that is important in these instances, says Srzentic.

She tells the story of Maria, a single mother of two children working as a gig driver in California. When her car broke down, she was left with no transportation or income.

Going to the library to fill in a form to apply for state support, she spent two hours to complete the form and had encountered repetitive questions and information gaps.

After submission, she received no indication whether it went through, and only found out weeks later that she did not qualify and would have to start over.

Srzentic and team conducted interviews with users to identify pain points, streamline processes and cut down application times from two hours to seven minutes.

Her team then developed the “empathy maps canvass”, designed to help identify a user group’s thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

These canvases proved useful in developing California’s webpage with abortion services information after the overturning of Roe vs Wade.

After governor Gavin Newsom declared California a “sanctuary” for women seeking abortion, Srzentic and team used similar interviews to design a webpage linking citizens to clinics, providing financial help for travel and lodging, and letting teenagers in other states know that they would not need their parents’ permissions to get an abortion in California.

The user interviews helped Srzentic optimise for accessibility and privacy: the webpage was translated into seven languages, written in a lower-grade reading level for those without strong English skills, and was built to be totally anonymous and subpoena proof.

Recreating digital government success in Montenegro

After former Prime Minister Krivokapic decided to build a government of experts in Montenegro, Srzentic took her learnings from California back home.

As with any good practice, it was not a case of dragging and dropping, but certainly the same principles of the “new tools” and potential for citizen participation against the traditional service model remained.

As with her time in California, her team was quickly faced with a crisis.

“Our systems were laid bare by Covid”, she tells us, “but that also created a catalyst for commitment and action”. The entire Civic Tech ecosystem, including civil society, banded together to make a Covid tracking website, whose data and researched informed the national Covid response.

The role of civic participation was once again crucial. More broadly, Srzentic’s team adopted the idea of empathetic government as a centrepiece of their work.

One example was the formal Empathy Challenges, which “enhance customer experience in [their] vital programs and services”.

This involved training ministers and policymakers in user research and active listening, as well as spending time with the citizens they supported to identify service gaps and points of frustration.

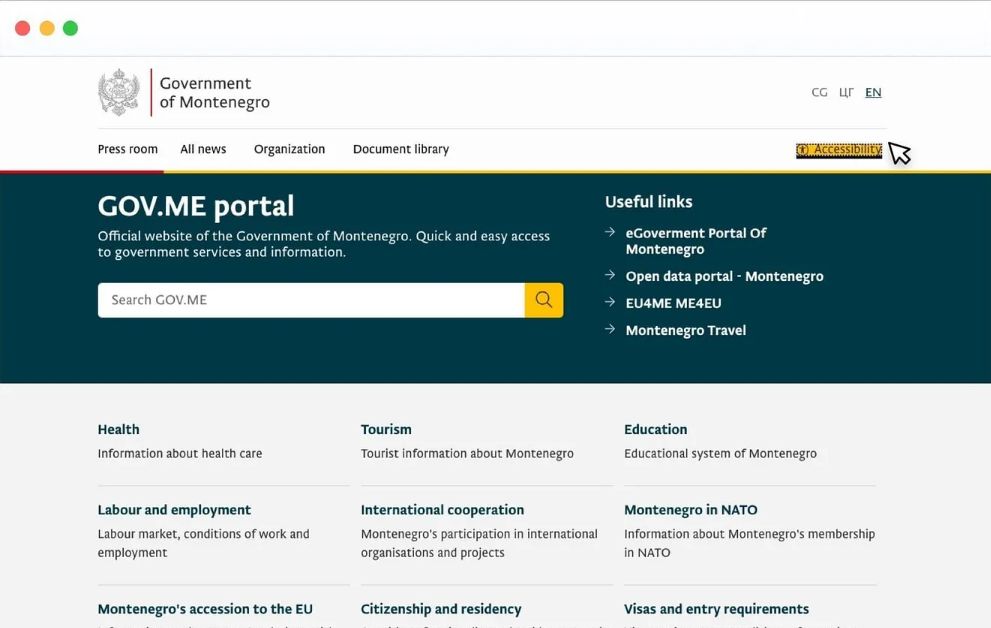

This approach reached its zenith with the reimagining of Gov.Me, the Montenegrin’s digital government platform which at the time had not been reinvented for 11 years.

To determine how to update the website, Srzentic’s team focused first on installing modern tools to track the challenges citizens faced with the websites (click through rates; surveys; time spent on particular pages).

They found that users were overwhelmed with the abundance of information on pages, and confused by the site map of the website.

As a result, they were able to focus on what mattered, not just aesthetics.

The newly designed website focused on clear communication and introduced a new visual hierarchy to reduce the “noise” of the websites. The site was redesigned in three languages – reflecting the heterogeneity of Montenegro’s population – and included accessibility options for the audiovisually impaired and a superior search engine.

Srzentic’s description is reminiscent of the UK GDS’s design principles, which they use to “make our work simple”.

Among them are the principles of “do less” and “do the hard work to make it simple” – “it’s usually more and harder work to make things simple, but it’s the right thing to do”.

In delivering the Gov.Me redesign, Srzentic team avoided another type of “noise”: the demand that governments build and deliver a shiny thing all at once.

But it is another of GDS’s famous principles that Srzentic draws on in her presentation, and that is central to her work: “strategy is delivery”.

This year, her latest project is Rebel Alliance, an open civic organisation which provides leaders committed to empathetic government with “tiger teams” focused on human-centred design.

“Leadership is a mindset; not a title”, Srzentic told GovInsider in an interview earlier this year and – even though she is no longer in the Montenegrin administration – she shows no sign of slowing that mindset down.

The story was originally published on interweave.gov.